96 Hands

96 Hands

A Room for Archaeologists and Kids

Pachacamac Archaeological Park, Lima, Peru

The Garden: The Third Cycle of Planting

A Collaboration between Studio Tom Emerson ETH Zurich and the Facultad de Arquitectura y Urbanismo, PUCP Lima. Research and survey, 17 - 23 March 2018, Design and Build Project, 18 June – 12 July 2018.

Welcome to the studio. To open our first semester at the ETH, we will ask you to design and build a structure from discarded materials, reclaimed and re-used to provide shelter and a place to meet - the primary purpose of architecture. Wooden palettes with nothing more to carry, hoarding with no construction work to enclose and old timber beams cut too short to span may appear today as rubbish, valueless and passed utility and even passed beauty. We will seek to find new ways to assemble them into a public space that transcends their origin. Using simple hand made assemblies, the modest cast offs will be mined for new constructional and structural potential. Gravity, hammer and nails and handsaws will form the grammar of the new structure.

But remember Vitruvius; alongside firmness and commodity there should also be delight. This not about junkyard chic; our entry in to the world of bricolage is about making beautiful things from the world that surrounds us, embracing scarcity as the font of invention.

Garden Rules

1. Each semester’s work is a finished project as well as a canvas for the next.

2. Think in scales: days, weeks, months and years.

3. Be carefull towards soil.

4. Work like a gardener with the precision of an architect.

5. Work like an architect with care of a gardener.

6. Be aware of the weather conditions and work with them.

7. See the weeding as the art of dividing the useful from the less useful.

8. Remove the soil from your shoes and maintain cleanliness.

9. Plant and construct to preserve and improve the existing condition.

10. Everything in the garden can be reused.

11. Unexpected garden projects can be added at any time.

12. The garden is a room from which nothing ever leaves.

The project will be in three parts, the first 24 hours will be an intense design laboratory to survey the assembled material and propose a structure that will transform and transcend the original materials into a new place.

This is not a competition but we will, collectively, select a proposal to build or combine several ideas into a kind of architectural skvader or even select only a fragment to develop into the complete structure – opportunism and flexibility are central to the creative bricoleur.

The second part and the most demanding will be the building. You will have just under two weeks to complete the task. Your ninety-six hands are the greatest asset but to organise forty-eight people to work effectively is also the greatest challenge. Anticipating the sequence and physicality of work will be as important as the aesthetics of your design.

The third part will be the celebration: to host events and talks and any other architectural experience you can conceive for the neglected but peaceful corner of ETH that the structure will inhabit.

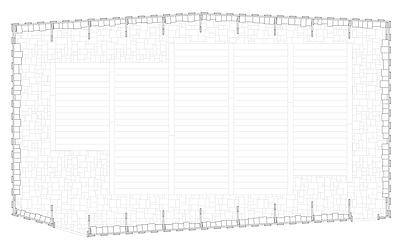

Some forty-five students from T5 Juillerat/Manrique at the Facultad de Arquitectura y Urbanismo, pucp Lima and Studio Tom Emerson at eth in Zurich under the guidance of Guillaume Othenin-Girard collaborated on a six-month investigation that culminated in a design and build project. Together they produced a structure for archaeologists and children to come together to discover the hidden history of Pachacámac. In this new structure, Archaeologists make their first examination of artefacts emerging from the digs, shaded from the punishing Peruvian sun and in view of the passing visitors and school children, who in turn perform their own exploration in the sandpits across the courtyard. At each end of the courtyard, new finds are stored in rooms enclosed by woven cane walls before being transferred to the archaeological museum for permanent conservation. The structure was collaboratively designed and constructed by the students in three weeks in July 2018, following a research programme earlier in the year resulting in the Pachacámac Atlas.

Desert Lurin Valley, picture by Géraldine Recker

The archaeological site of Pachacámac is a most extraordinary constructed landscape. Situated on the outskirts of Lima, Pachacámac covers about 600 hectares of land. The pre-Columbian citadel made up of adobe and stone palaces was first settled around a.d. 200 and flourished for about 1300 years to become one of the biggest and most important of these complexes in Peru. The site is the host of numerous layers of civilisation, overlapping each other at this important node of the Qhapaq Nan network of Inca trails, connecting the Pacific Ocean to the Andes. Thus, it represents the full transect of the Peruvian landscape, from the mountains to the coast.

The northern two thirds of the site comprise unexcavated open land awaiting future studies; this monumental area is a significant archaeological site with active excavations and on going discoveries of artefacts and architectural remains. With the construction of the National Museum of Archaeology underway, the government aims to restore this stretch of land to its former grandeur by transforming the site into a new centrality, embedded within the urban-fabric of the city of Lima. Yet Pachacámac is currently perceived as a void, a patch of open-desert inhabited by ruins, caught between the baffling growth of the capital and the mouth of the Lurin River–the last remaining agricultural valley of the region. Its edges are constantly under the threat of encroachment by informal settlements, such as the Julio Cesar Tello neighbourhood, or land invasions, the latest of which as recent as May 2015.

Given the proximity to Lima and the inevitable encroachment of the city into the territory, the project compelled us to ask how a culture can live with ruins, to comprehend what they represent, without being suffocated by their monumental presence. In order to restore the balance between the urban, the natural, and the cultural heritage in the city of Lima, the focus of conservation must shift from the mere preservation of physical archaeological sites, which have lost their meaning and value for the inhabitants; towards revealing and making legible the ancient knowledge embedded in their built heritage and their relation to the territory.

The Room for Archaeologists and Kids, collectively designed and built by students from the Department of Architecture at the Pontifical Catholic University of Peru pucp and Studio Tom Emerson eth Zurich, concludes a six month long collaboration on the archaeology of the territory.

The first phase after the Atlas was a 48-hour design workshop in groups of three based around site proposed by the director of the Museum, Denise Pozzi-Escot and the available materials. The workshop was a way of exploring the widest field of ideas before coming together around a single strategy. We selected a project to provide a direction to which we added elements of other proposals in order to complete the design. The constraints presented by site and material means were not thought of as barriers but as generators for design. Timber was our main structural material. The success of the group proposals lay in the simplicity of construction and relationship to other materials such as adobe bricks, woven cane and plastic textiles.

The final phase was the most intellectually and physically demanding — the construction itself. We had just under three weeks to complete the task. The team was the greatest asset but to organise nearly 45 people to work effectively was challenging. Anticipating the sequence and physicality of work was as important as any conceptual or aesthetic decisions.

The collaboratively built structure structure will support the social outreach programme of the archaeologists based at the Museum of Pachacámac.

Finally, it is our intention to repeat this project at the start of every semester using the same material again and again. Your structure will be the first of a series of transformations of the same material. We ask you not only to consider the origins of things and their immediate potential but also their futures beyond.

We must give special thanks for great support to the Block Research Group, especially to Marcel Aubert and Prof Dr Philippe Block.

Monumental Part, drawn by Severin Jann

Borders & landuse, by Sara Sherif

Manufacture & Industry, by He Shen

Manufacture & Industry, by He Shen

Manufacture & Industry, by He Shen

Irrigation Systems and Hydroponic Greenhouses in the Lurin Valley, drawn by Lucio Crignola