A BIT OF MATTER AND A LITTLE BIT MORE

A Bit of Matter and a Little Bit More

Architecture today is caught in a vicious cycle of contradictions; damned if you build, damned if you don’t. Damned for its contribution to climate change, damned by its absence to provide for a growing population. Virtually every site in Zurich’s city limits is reserved for development. Densification remains the dominant paradigm for good spatial and social governance. And while densification is slowly bending to the winds of climate change with more sustainable construction, community participation and circularity, the legacy of concrete is at the heart of these contradictions. Half of buildings in Switzerland are made of concrete which include some remarkable architecture while over third of the Zurich’s ground is sealed under concrete or asphalt, enough to significantly exaggerate the impact of global warming. Enviable architectural heritage is literally and conceptually intertwined in the need for more and less.

Architectural observers often admire Switzerland for the quality of its concrete and railways, thinking, quite reasonably, that one efficiently facilitates visits to the other. But the relationship is more than convenience. Concrete and infrastructure mutually constructed one another. Tunnelling pierced mountains with railway lines supplying aggregates and cement to meet the building demands of a newly mobile workforce. The sculptural forms of Max Vogt’s concrete SBB buildings are concrete monuments overseeing the extraction and displacement that made the railways and built the modern nation.

Along Zurich’s Gleisfeld, new ecologies have taken root within the micro-spaces of granulated concrete and stone, creating habitat for many species away from the forces of development and human occupation. Occasionally, they drift inland where the masterplans have not yet seized the real estate opportunities, like at Hermetschloo where concrete architecture and ecology show signs of new alliances. It is enclosed by railway tracks to the north and a busy road to the south, bending the site into the shape of a lens one kilometre long. A ruderal ecological corridor passes through a loose arrangement of some of the most innovative industrial buildings.

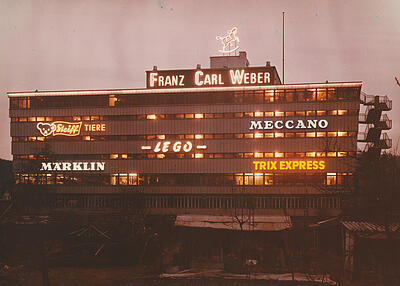

In the mid 1950’s, Franz Carl Weber commissioned an inverted concrete ziggurat to store its toys on the inside and, breaking the Swiss tradition for discretion and sobriety, festooned the outside in a playful collection of neon signs, both Duck and Decorated Shed. It is attached to one of Max Vogt’s tour de force in concrete for SBB along the Gleisfeld. And if concrete defines these railway buildings, the Schnellgut Bahnhof gives the most explicit and refined expression to the profound relationship between Swiss concrete and trains. Elegant precast shells cover the station in repeating twenty-five metre spans matching the railway carriages that brought them into the city.

If Schnellgut Bahnhof gives architectural form to a national infrastructure, the Micafil factory on the southern boundary assumes a more cosmic profile, built in 1977 when solar architecture still promised to free architecture from fossil fuels after the Oil Crisis. And while the solar panels have long since disappeared, the profile still optimistically leans upwards towards the sun. These buildings are made of highly specific relationships, evolved over time and across geographies. There is no pure form, or abstract space at Hermetschloo. Every building asserts deep relationships to its use, production, material, territory, and cosmos.

Since the 1990’s industries and logistics have gradually left the city. Luckily, new uses and users have filled some voids. Franz Carl Weber warehouse has been refurbished and found a business cooperative to use the building productively. The future is far less certain for the Schnellgut Bahnhof, Micafil and all the species that have established the ecological corridor through the site. Loo from Hermetschloo means small woodland, an evocative reminder of former conditions before urbanisation. It is remarkable that there has been no significant plan for the place since 2005 and the site remains largely in its first industrial condition. But it is in a designated tall building zone. The pressure to develop is tangible, inevitable.

This semester, we shall look at how this place can develop new alliances and repair old ones worn by use and neglect. What will become of Schnellgut’s heroic interior? Can Micafil re-turn to the sun and show us what more it can do? Can ecology grow larger and more complex for the benefit of all species, maybe even humans too, whose needs for new habitat are real? Can circularity make sense of concrete’s entanglement? While windows, doors, metal and timber are eagerly reclaimed today, signalled by reassuring patchworks of irregular assemblies, concrete is less cooperative. Concrete still relies on an elsewhere along the tracks, where the messy knots of cement, sand, gravel and steel can be disposed of out of sight. Just as cement, sand and gravel, extracted far away, arrive miraculously on the back of a train, it will disappear again to be granulated and dispersed as aggregate or landfill. Can Hermetschloo be its own quarry as Switzerland’s geology was for its railways? Can density exist without excess?

Our explorations of concrete environments in the city will follow a hands-on collective project in the studio garden to re-use and re-place fragments of previous concrete and brick constructions in a new landscape setting.

The design studio will run in parallel with the elective Repair: Keep in Place led by the Chair of Silke Langenberg. It involves an integrated seminar week of practical building exercises in repair. Enrollment in both the elective as well as the seminar week are strongly recommended.