Entangled

Entangled

Prologue: a view is a two-way responsibility

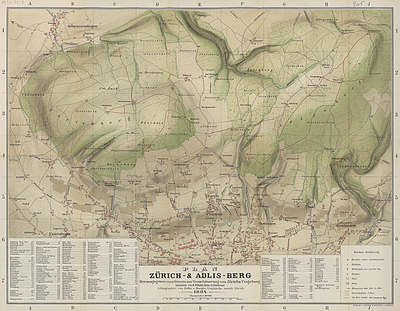

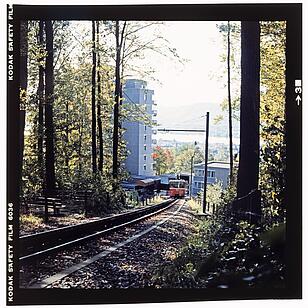

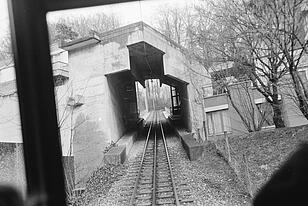

A forest, a funicular railway to climb the mountain, a hotel, or, a landscape, an infrastructure, a building. That is the sequence leading to the Dolder Waldhaus and eventually the Dolder Grand Hotel. All in pursuit of a view, the picturesque sensibility of early nineteenth landscape design that turned landscape into an idealised picture of nature. What had been framed around large country houses for the aristocracy turned into hotels and restaurants for an emerging industrial middle class to enjoy previously unheard-of recreation and tourism. The view was, and remains today, the most prized commodity, an idea of a perfect nature outside of human action.

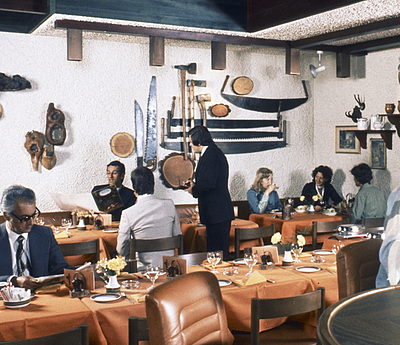

The forest and funicular remain but the original national romantic (heimatstil) Waldhaus, built in 1895, was demolished and rebuilt in the 1975. The existing Waldhaus reflects the architecture of time in scale, composition and concrete materialisation but never forgets its original desire to capture the view. Pre-industrial hand saws, axes and slices of tree trunks decorate the restaurant walls evoking a pre-modern natural idyll. But landscape practices have changed as radically as architecture. The forest is not the ancient primordial nature we like to imagine, nor is the lake visitors admired from the breakfast terrace. Like all the contemporary landscapes, they are both highly managed and regulated to serve social, economic, aesthetic and environmental ends. In short, they are designed.

But unlike the landscape, buildings are easily replaced when they are perceived to be beyond use – which in reality they very rarely are. And after failing to fulfill expectations as a larger hotel and then housing, a competition was held in 2011 to replace the Waldhaus a second time with a new block still firmly dedicated to the view. Over a decade later, the Waldhaus is suspended in uncertainty, a condition euphemistically called meanwhile-use while waiting for economic opportunity for replacement.

Re-use is not only desirable but necessary. But how and to what end? Repair, restore, refurbish, preserve, demolish, conserve, maintain, reuse, recycle, up-cycle, upgrade. From repair to upgrade we can insert an increasing number of words describing design and making, associated with working within the existing. Each verb denotes a position, a method, an attitude towards the past, the present and the future carrying specific ways of seeing and a way of doing, they testify how the ground of architecture and design is shifting. There was a time, not long ago, when architecture and design were firmly indexed to all things new. The more modest but universally practiced acts of everyday maintenance, adaptation and repair have continued largely unnoticed in the background of the new.

The discovery that steel and concrete share the same thermal expansion coefficient transformed the 20th century. If you encase steel bars, which is excellent in tension, in the concrete, which is excellent in compression, you produce the wonder compound material to emancipate the world. Together they act in sublime harmony in the structure of the Waldhaus. Separated they fall in an entangled mess of wire and rubble, aggressively opposing any kind of future reuse. We shall challenge the perception of waste and discover the possibilities of use. But while methods of building re-use continue to grow, we shall look to the landscape for strategies of maintenance, management, repair, regeneration, and restoration of habitat including the building and its occupants within the environment; forest, mountains, meadows, geology, topography, water, the seasons, climate change and all the species within it. We can no longer afford just one point of view.

A Master Thesis Semester in collaboration with

Professur Voser, Professur für Landschaftsarchitektur