What's in Store?

What's in Store?

Apple store, after strip out, Bahnhofstrasse, Zurich, 2020. Photo Boris Gusic

"The Anthropocene marks severe discontinuities; what comes after will not be like what came before. I think our job is to make the Anthropocene as short/thin as possible and to cultivate with each other in every way imaginable epochs to come that can replenish refuge."

Donna Haraway

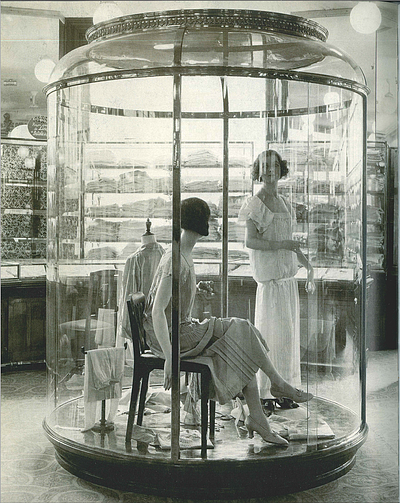

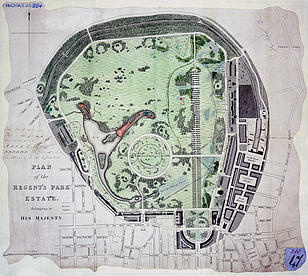

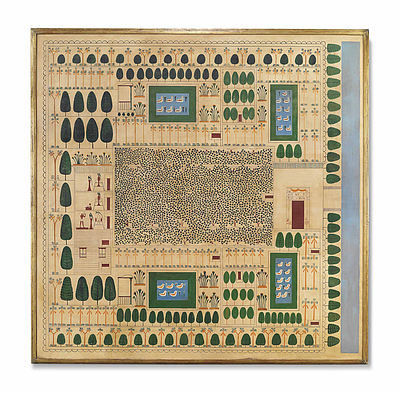

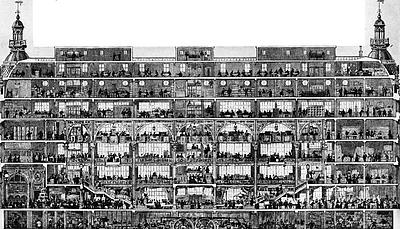

Shopping is over. Just like that. The social and economic revolution that gave form and style to the nineteenth century city has slipped into the palm of our hand leaving the city centre in search of renewed purpose. But if the human transactions are moving from over the counter to the digital ether, the desires, freedoms, walks and talks, will not be so easily privatised. The industrial revolution produced a previously unimaginable quantity and variety of things for which the department store was invented – following the prototype of the Crystal Palace (1851) a detournement of the gardener’s greenhouse - and produced an irresistible spectacle for the rising bourgeoisie. The architecture and in particular large glass shopfronts rivalled the marvels of museums and gardens. Behind glass, everything is seductive.

No doubt the dual reflection and transparency of expansive glass vitrines brought with it a new spatial experience, describing complex enclosures and openings, fusing all materials together to form the contemporary city. And perhaps it was glass itself that most changed the nature of public space. It promises openness through transparency but delivers exclusivity in reflection.

Far from being banal, mono-functional spaces away from the richness of metropolitan culture, the edge of cities are vital and multi-layered territories where work, leisure and sport are integrated in productive and ecological landscapes that have a great deal to offer contemporary life. The diversity of architectural types and landscapes documented in the Friesenberg Atlas could be seen as attempt to describe the nature of place. The design for Vereins made last semester have also demonstrated how small community organisations live together, interconnected with infrastructures, diverse topographies and ecologies to create a natural territory. And how even the smallest interventions can transform an ecosystem. Adjustments to walking patterns, to enclosures and openings on the surface change everything below or besides. Reimagining former architectures can create new things from the ends of others. It is a big space and a small space. Like the Eames’ The Powers of Ten, it is logarithmic, oscillating between the miniscule and the epic. Drawing the Atlas led the way with lines that literally describe the walk through the city, the blade of grass points to the lie of the land. Most of all, the Atlas and Verein have shown, far from being amorphous spaces, powerful spatial structures can bring beauty, biodiversity and human action into what can be seen as The Great Interior. This semester, we shall explore how larger structures bring another social, material and spatial disciplines to these edge spaces. We shall design an arena, a public building for performing and watching sport (and perhaps more). With origins as landscape structures in ancient times, arenas are typically defined by ground; dug in, cut and sculpted earth and stone. Then they rose out of the ground as pure-structure never fully enclosed. We will look for how structure and materiality can be the conceptual and technical engine of architectural design.

We shall frame the design process in terms of the complex and very much contested field of energy. What is embodied energy? It concerns the body of course, the athlete and the human physicality the arena celebrates. But it also concerns the urgent field weighing and measuring our resources as we attempt to recast our use of resources. It concerns design. The body may be analogous to our material world; fragile, weak, requiring extreme care to ensure its health, wellbeing and happiness. But also strong, inventive, resourceful and capable of extraordinary good just as it can inflict untold violences. How are these measured and calculated and what value does it have as our culture runs blindly towards catastrophic climate change? How do we design another great interior?

When an ancient tree falls in a closed canopy forest, far from being the end of life, light enters the dark space, “mixing new nutrients into the soil from debris, and initiating a race for succession.” [1] The old tree simply and naturally makes space for the new. This universal cycle, which is as much spatial as it is biological, may explain at least in part, the fascination for ruins in the modern era. In the nineteenth century Romantic imagination, the ruin showed architecture at its most pure, freed from the burdens of complex function, at one with nature. But today such processes may be more than nostalgia, they may just be the beginning of another age.

[1] S Denizen, The Flora of Bombed Areas (an allegorical key), The Botanical City, M Gandy and S Jasper (eds), Jovis, 2020, pp 40.

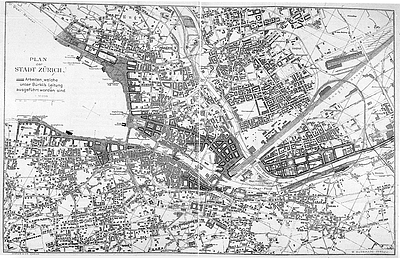

But Zürich’s main shopping street was not shaped only by the retail revolution. By the time the first iteration of Zürich’s Hauptbahnhof was built in 1847, the city walls had already been destroyed and the ditches sealed. Protest and disease are recurring themes in the city’s history. Textile workers’ revolts and the social divisions between town and countryside sparked the uprising in 1839 and the destruction of the old fortifications. Silk merchants converted their massive wealth and property into the banking institutions of today’s city, their houses and gardens forming the footprint for metropolitan expansion. Following cholera epidemics of the 19th C, the muddy ditch, the Fröschengraben was sealed over to become the Bahnhofstrasse, and with it the last traces of an agrarian society. Commerce, protest and later civic action led by Bürkli transformed a town on the river into a city on the lake.

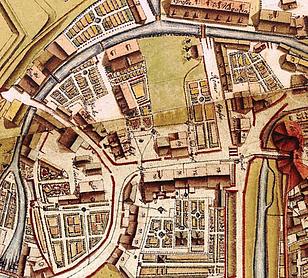

The gardens and streams of the 18th century disappeared under stone and concrete as the city reached deeper into the block filling it with loading bays to supply our shops and equipment to keep them cool. The excesses of spaces and things that caused irreversible climate change have finally provoked a reaction in society and most urgently in architecture.

The provocation that ‘shopping is over’ which opened last semester HS20 has turned out be truer than imagined. Department stores are falling around the world. We will consider a future for the legendary Zurich department store Jelmoli. Not because it is failing, but because of its continued success. Jelmoli’s evolution has not only witnessed the emergence of metropolitan Zurich, it has participated and even anticipated many of the urban and social transformations which are once again pressing in our own time.

The future department store lies within the existing walls if only it were allowed to diversify naturally. We need to shift our attention towards what already exists, to be attentive to architecture, materials and techniques which have given us the spaces of everyday life. Today’s new reality requires us to look more closely, to document, to excavate, to release new spaces in existing fabric and breathe new life into the city. Each stone block, steel column, sheet of glass, plasterboard partition has been placed in space according to the rules and needs of its time. The architecture, reimagined as an Atlas which can be edited, cut, thinned, renewed with the precision of the architect and the care of a gardener.

We will continue to work in our garden in parallel with our architectural journey. Working together, we will begin the next chapter of the garden. We will establish a new series of rooms in the landscape in parallel with those of the studio and of the city. And, weather permitting, use the rooms in the garden as a studio space. After a semester of interior confinement, we will use our spaces to maximise our time together and our time outside, in the garden and in the city. Or is the city already a garden waiting to be rediscovered?

You will be designing two rooms, one interior and one exterior and, most importantly, the membrane that holds them together or separates them. Like Split or the spatial transformations imagined in romantic ruins, the city will change again. Can a new natural city emerge from the interaction of two rooms? Can glass still provide the magic encounter? These two rooms will start with the architecture and nature of the city of today and project them with all the force of current events into the future. The city will be different. Architecture will be different. Materials will be different. Nature is different. But they are rooted in where we came from, be it a muddy ditch below the street or a distant land.

The new rooms will be found in the existing city. They may be turned inside out, reversed, excavated or filled but all forms of re-use because as Bruno Latour has famously stated, design is only ever re-design. The end of retail could precipitate a radical transformation of the city, recasting what exists in a new natural order sensitive to the needs of humans and every other species with whom we share the planet but have expelled in our drive to consume.

The porosity of the city is central to its ecological recovery. New species of plants, insects and mammals are rediscovering habitats in the unseen corners of the city. Perhaps now is the moment to welcome them into the heart of things by looking at urban development in reverse. But not a return towards origins per se, but to acknowledge that the world is cyclical and after the growth comes decay followed by recycling in order to grow back stronger, more diverse and resilient.

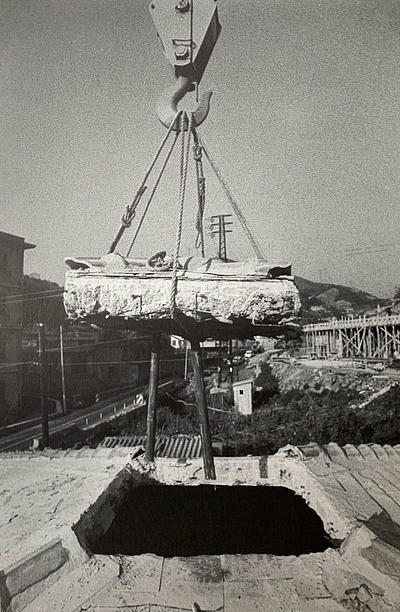

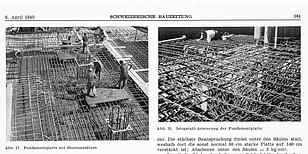

But as much as this question may be about the future of cities and the culture of retail, we shall approach the project by direct means of architecture. We shall initiate a series of simple constructional operations on the site of Jelmoli at Seidenhof; the first is to record what is there through the act of surveying; measuring, photographing and drawing what we see. The second will be to excavate material from the sealed city fabric (like the ancient tree falling in the forest) to create or recreate new spaces for new ecologies. And the final stage will be to re-inhabit the excavated city to propose the future of retail that contributes to the human and non-human ecologies of the city.

The Atlas

The act of surveying will be expanded by what cannot be seen but can be deduced from archives documents and social histories. And what is neither visible in the place or contained in records can be induced by speculation into and beyond the walls of Jelmoli. The materials extractions and transformations that constitute the built and the supply chains interacting with social habits to constitute its uses. And finally, the traces that bear witness to the passage of time.

Excavation

With the Atlas, we shall ask you to excavate the built fabric of Seidenhof; to introduce spaces for an enlarged and more diverse environment. By stripping away layers of construction or cutting segments, we will ask you to open the city block for re-inhabitation. The new spaces may be invented from within the city block or simply rediscovered from its evolution. Their potential lies in how they will extend the range of environments for human and non-human users and in the re-use of the materials produced in the process.

Inhabitation

With the Seidenhof opened for earth, light water and air to play their natural role, you will design the next layer of re-inhabitation by Jelmoli. How can the future department store be model for a botanical city? How can the interaction of environments respond to the social, ecological and commercial needs of the city? And most importantly, what how will architecture and construction find the form and expression that connects the past with most pressing issues of tomorrow?

Growing

We shall end the semester where we began the last one, in the garden. We will collaborate with the ecologists of the Crowther Lab to design and plant an experimental garden combining soils and plant species to test resilience and growth in relation to human uses. The Crowther Lab will introduce ecological themes in three lectures at the beginning of the semester. And we will put that into practice in the final two weeks when we can work together outside in good weather. If, by the end of May, the pandemic continues to make it impossible to come together, we shall offer an alternative, but we very much hope we can end as we started, together.

Jelmoli's Zurich

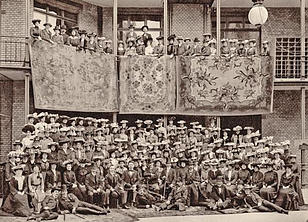

As with so many stories of the city, Jelmoli’s origins are in textiles. In 1804 the Ciolina brothers open a store in Mannheim importing Italian textiles and garments. The journeys between Valle Vigezzo in northern Italy and Mannheim bring Switzerland firmly into the frame and in 1826 they open a store in Bern. But Zurich is the fastest growing city in Switzerland in the early nineteenth century. Booming trade centres on the Limmat river. Boats navigate between buildings and emerge out of the flowing water. By 1833, the business has been passed down to a Ciolina son in law, Jelmoli, who opens the first clothes shop at Schipfe on the banks of the Limmat below Lindenhof. It is an instant success thanks to its prominent location and, perhaps more importantly, to the introduction of fixed prices and mail order service.

But the pioneering spirit of Jelmoni’s clothes was not to everyone’s taste. The peasant’s revolt of 1839 in Paradeplatz and Münsterhof took aim at the liberal values of the emerging urban culture, Jelmoli’s modern attire were more evidence of the decadent and ungodly lifestyle of the progressives. The protests, along with trade problems with southern German states almost ruined the business.

The solution was both local and global. Jelmoli turned away from the former suppliers in Germany sourcing textiles from within Switzerland and colonial sources. Their growing supply and distribution alongside the customer base lay with the introduction of the railways and the consolidation of the post office in 1849 and the telegraphs a couple of years later. The new interconnected era moved people, goods and ideas in unprecedented quantity and speed. While Jelmoli embraced the possibilities of the new Swiss infrastructure, news of the department store would have stimulated his entrepreneurial spirit. The Great Exhibition of 1851 was the event to open the consumer age. Paris, London, Chicago were opening stores where leisure blurred with traditional trade, where women could go about their business unaccompanied and necessities of life folded into urban spectacle. And if geography prevented people from participating in person, catalogues and mail order would satisfy the most remote customers. Telegraph and railway networks took shopping online long before the internet.

Jelmoli had already moved to larger premises at Münsterhof in 1837 and opened a short-lived outpost on Paradeplatz in 1880. And to meet the growing demand of mail order during the second half of the nineteenth century Jelmoli bought a warehouse at 6 Sihlstrasse. Nearer to the new Haupbahnhof, it confirmed the department store’s position at the heart of the modern story of central Zurich.

Jelmoli can be seen as a story of mobility and urbanisation; the mobility of goods and fashions to move across the world at unprecedented speed is matched by social mobility of an emerging middle class, enjoying the spectacle of the modern city, and the benefits of international trade and colonial imports.Although Jelmoli is not credited with the great set pieces of either Escher or Bürkli who created the institutions and infrastructures that defined the emerging Swiss confederation (ETH, banking and the railways by the former, Bahnhofstrasse and the metropolitan lakeside by the latter), Jelmoli provided the setting and style for the people of Zurich to live the modern industrial age.

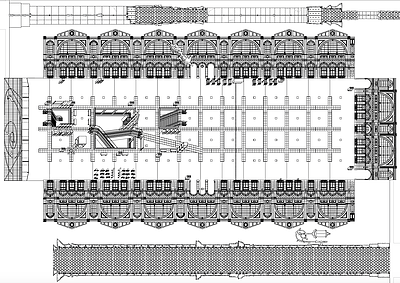

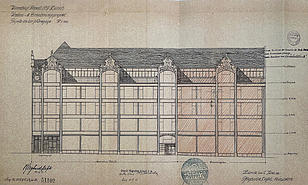

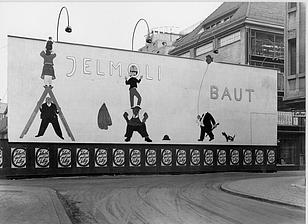

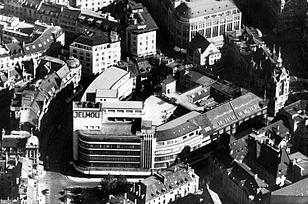

However, if following Jelmoli across the trade routes of Europe is to witness the nineteenth century at close quarters, then one only has to stand still on a single site along Sihlstrasse to witness the twentieth century. Following decades of trading near the Limmat river and distributing mail orders from Sihlstrasse, Jelmoli buys the neighbouring plots and, in 1898, builds his full department store to match Paris, London and Berlin. Four storeys of fine cast iron structure created the greatest shopfront Zurich had ever seen. With clear references to Art Nouveau tracery from Vienna, Brussels and Glasgow, Jelmoli completed the new metropolitan Zurich. Silhstrasse, also known as Seidenhof (or Silk Court) became the site where Jelmoli would consolidate its place in the architectural, urban and social history of Zurich. Over the coming century, Jelmoli would first rebuild and then extend the department store plot by plot until the entire city block was completed.

Zurich’s wealth was made with textiles. Seidenhof was established in 1592, kick starting the silk industry whose prosperity would lead to banking that defines contemporary Zurich, at least in the eyes of the world outside. The silk merchants built grand houses and gardens which largely define the urban grain today. The houses grew larger but without pretension, reflecting Zwingli’s protestant teachings. However such restraint did not apply to interiors. Behind the modest facades great carved and painted interiors testified to the wealth and culture acquired through silk. Entire rooms are on display in the Swiss National Museum. Gardens were also originally utilitarian performing a series of practical tasks of laundry, sanitation and food production. In time though, the gardens were also tended for pleasure with flower gardens.

But with urbanisation come all the challenges of public health. And private land not developed for commercial expansion would be covered in services of civic responsibility. In some respects, echoing the covering of Froschengraben to make Bahnhofstrasse (following a cholera epidemic), Seidenhof was built over until the entire ground was sealed. Throughout the neighbourhood, the grand houses and gardens of the silk merchants were gradually replaced with banks and its attendant commerce. Retail and department stores spread with electrification. Jelmoli turned the city into an urban vitrine for the consumer society. The new central district did not prevent its use as the site of protest throughout the twentieth and twenty-first centuries but the crowds attending the opening of the new Jelmoli in the 1938 testify to a new type of public life; display, retail, fashion and public space fusing together to create the age of leisure. Gardens become service yards until they are themselves fully built. The porous city is sealed.

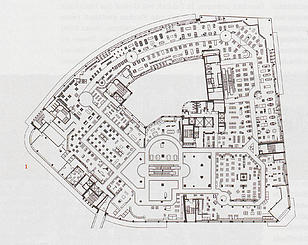

With one foot belonging to the flaneur and the other in search of glamour or a bargain, the experience economy continues to grow and Jelmoli keeps up by filling the city block, building by building, until its own plan resembles that of a garden, a place of promenade, conviviality and pleasure. Each building reflects its time. The architecture takes the form of façades and atria, the two elements where the city and nature find expression. But beyond the atria, light is electric, climate is mechanical and the products are global with just enough local craft to keep the real consequences of modernity at bay.

Until the end of the twentieth century, economic and urban growth seemed to have only direction of travel – endlessly upwards. But with the combined consequences of digitisation since the 1990’s, global economic crash in 2008, climate change and Covid right now, we find ourselves in a moment requiring profound and accelerated re-evaluation.

The presence, control, promotion or eradication of biodiversity has been largely a matter of municipal government at an infrastructural level and to a lesser extent by grass roots activism at a specific spatial scale. Water, the life source of humans, flora and fauna has been managed by the city. Public health, including the cholera epidemic which led Bürkli to cover the Froschengraben to make Bahnhofstrasse, has stimulated the developments of inner city infrastructure. Indeed Bürkli’s plan for Bahnhofstrasse is as technically complex and comprehensive below ground as it is elegant above. And by extension, such infrastructures have determined the subsequent urban spatial and ecological character of the city.

Development in Jelmoli’s surrounding plots operates according to intense market forces that have largely avoided participation in ecology except where it was to commercial advantage. But it may be claimed that climate change and, to an as yet unknown extent, the pandemic will not only change the politics of urban ecology of our time, but transform its commercial realities. The balance between development density and ecology in the city centre which has for decades been firmly in favour of the total covering of private land in buildings such as Jelmoli will change, partly for the health and wellbeing of life, but equally for economic viability of the centre, or of the department store. Garden and micro parks are maintained, but very much controlled and in service of the surrounding real-estate.

So how will Jelmoli face the remainder of the twenty-first century? Department stores are and have been closing all over the world. At the same time, world cities are searching for methods to address climate change. Re-naturalisation is here; in policy and in reality. Paris is turning the Champs-Elysées into a park. The porous city or sponge city may be new brand names for ecological recovery but the phenomenon is real. New species of plants, insects and mammals are rediscovering habitats in the unseen corners of the city. Foxes are now a common sight in Zurich. Climate change continues to redraw the geography of birds and insects. Perhaps now is the moment to look at urban development in reverse. But not a return towards origins per se, but to acknowledge that the world is cyclical and after the growth comes some decay, some recycling in order to grow back strong, more diverse and resilient.