Standard

Standard

Zurich Railways

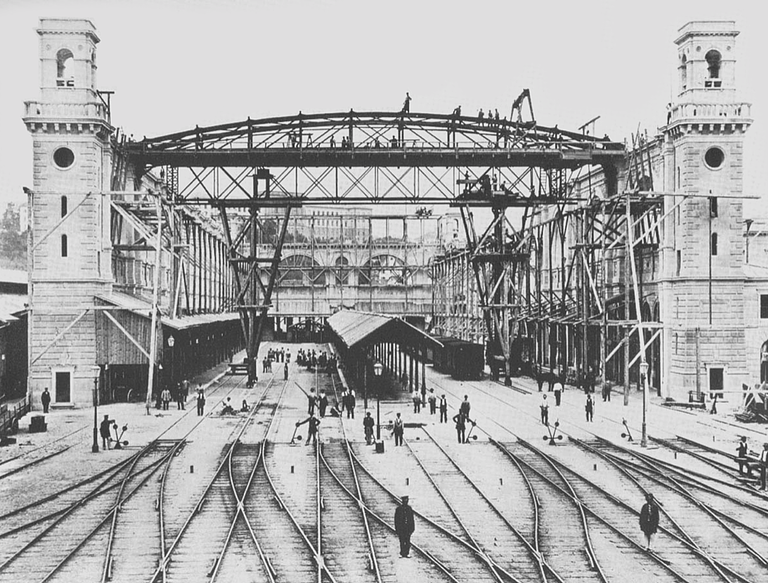

Railway tracks have a standard or gauge. Without it, trains could not carry us across a continent (with some notable exceptions). In the track-field that winds like a river into Zurich’s Hauptbahnhof, one finds this standardisation surrounded by the fluid, irregular and specific.

Construction and materiality will remain the driving forces in our design studio, but standards will be used to reveal compliance or deviation from social or architectural norms. The collective Atlas survey, which places measuring and observation as the first act in design, makes use of already established standards for drawing and perception.

Today, architecture is increasingly standardised by the product catalogues of manufacturers and tightening regulation. And even landscape is subject to standardisation, at least since the beginning of industrial agriculture. Meanwhile nature continues to evolve its own standards for survival and proliferation, but these are mostly invisible. We shall extend these studies of standards into the heart of contemporary architecture.

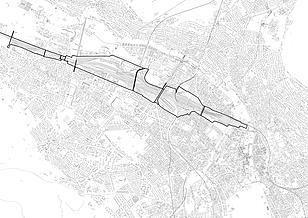

And no landscape is more regulated than the one which gathers the twinned lines of steel from every city in Switzerland and Europe to form an orderly entry to Zurich. As roads and highway logistics increasingly take over the management of goods entering and leaving the city, railway sidings, depots and warehouses are left vacant. New spaces appear intermittently, barely coalescing into a singular space at the heart of the city: what could be called a railway room.

Unlike Zurich’s other great landscapes, the track-field is six kilometres of uncertainty. Europeallee has already claimed the most central stretch for neo-liberal metropolitan development. However the fringes of this transport infrastructure have yet to be given a coherent form. Could the railway room be one space like the lakes or forest or is it a necessarily fractured element, driving a hostile void through the urban fabric? The engineer Arnold Bürkli transformed the lakeside in Zurich through new public spaces, edges, gardens, pavilions and real estate opportunities, into a setting in which the city could find its collective heart. Can we do for the railway room what Bürkli did for the lake and turn an uncertain boundary into a life affirming space?

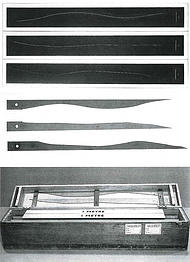

We will produce an Atlas of the railway room, that will range from the engineering of the railways, the social life that weaves within it, through to the flora and fauna that exists in an exceptional ecosystem protected from human activity. In autumn semester we shall develop a new urban landscape: an edge to match a grand lakeside or riverbank. Whether treating the ground or an architectural object, we shall explore the potential of standardisation in contemporary construction to create new spaces beyond the imagination of a real estate developer or a building product catalogue. We shall search for the soul of the city in the norms of our epoch. Mies Van der Rohe did it when he placed the rolled steel section in the American landscape and Marcel Duchamp gently disturbed the ultimate rule of the metre with his Three Standard Stoppages.

The scope of the design project in autumn semester is grand but will be explored at multiple scales. The scale of urban landscaping on paper or in models will be matched with a hands-on construction in our garden, which will engage the first standardised product of them all: the brick. This hand-sized block of baked earth has been so powerful that it has accompanied and at times even generated the great periods of architectural history. We shall start the year with a group intervention in the garden to build new spaces and structures. And in spring we will continue to add another layer of planting.

In the design studio in spring semester, the new urban landscape of the railway room will be the setting for new architectural development. Once again, we shall use the constraints of the standard as the engine for beauty and innovation in architecture.