Recycling Melting Blowing

Recycling, Melting, Blowing

24-29 October 2021

Faking it

for real - this time

18-24 October 2020

Faking it

14-21 March 2020

London’s Natural History

22–28 October 2017

There is a certain alchemical magic in the transformation of sand into glass through fire. At around 1320 degrees the syrupy blob of glass is liquid enough to blow into, resulting in a bubble that embodies the human breath.

From solid to liquid and back – as long as the glass remains free from contamination this process can be repeated endlessly, making it a prime candidate for recycling.

Tracing glass from the bottle to the recycling plant and back into use, our journey will take us through the industrial landscape of Switzerland, all the way back to our garden at the Hönggerberg where we will directly recycle glass into new forms.

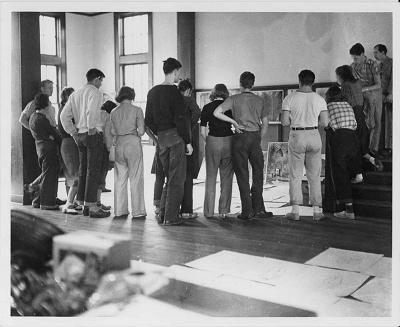

We will engage in the process of glassblowing in a way probably most comparable Dale Chihuly. The master glassblower had lost one eye in a car accident and thereafter was dependent on assistant glassblowers to execute his distinctive designs. Chihuly choreographs and deploys his glassblowers and crews like actors on a stage. “I’m also fond of drawing parallels between the way I work and the way an architect relates to his group”, he says.

In artisanal glassblowing, the size and shape of the glass product are hugely dependent on the artisan’s body: In the case of “broad sheet” glass, the size of the bubble is limited by the artisan’s lung capacity, their height, and their capability to swing the blowpipe. In order to create larger sheets, the height of the artisan must be increased or the lungs of the artisan replaced – e.g. by compressed air.

In 1886 the Swiss engineer Gustave Falconnier patented a hexagonal brick made of glass blown into a mold which made glass insulating as well as structural, whilst still allowing light in. Glass became an industrial commodity without which modernism’s mantra of “light and air” would never have emerged. From stained glass church windows to curtain walls, it could be argued that no other material bridges such a large ideological gap in architecture than glass.

The Ise Jingu Shrine in Mie Prefecture, Japan is a reproduction. It has been demolished and rebuilt from scratch on a 20-year cycle 63 times, holding it in a paradoxical state; forever new and forever ancient and original. Is the temple a fake? What is a fake? Forgery, fabrication, fake and feign all have their etymological origins in words for the inventive acts of shaping and moulding. Can we consider the art of forgery, then to be a valuable creative act, a form of cultural heritage?

The 1972 John Berger BBC series, ‘Ways of Seeing’ begins with the presenter cutting a face from Botticelli’s Venus and Mars, a disturbing and provocative act even seen on YouTube almost 50 years later. This face has however already been extracted and distributed millions of times in catalogues, posters, books, catalogues, films, copies and fakes through photography and reproductions. The meaning of a painting no longer resides in its unique painted surface, nor on its immediate context.

We know most of the works of art that we love by looking at them in reproduction. It is images of these reproductions that we look at in books and carry around in our heads, yet being face to face with the originals can give us a qualitatively different experience. Vernon Lee describes this real relationship with physical artworks as a spontaneous and organic attraction, an immanent and unconscious relationship with the things in her environment. But can a forgery incite the same phenomena? “The important decision to make when you are talking about the genuine quality of a painting’ explains Clifford Irving, biographer of famed forger Elmyr de Hory, ‘is not so much whether it’s a real painting or a fake; it’s whether it’s a good fake or a bad fake.’

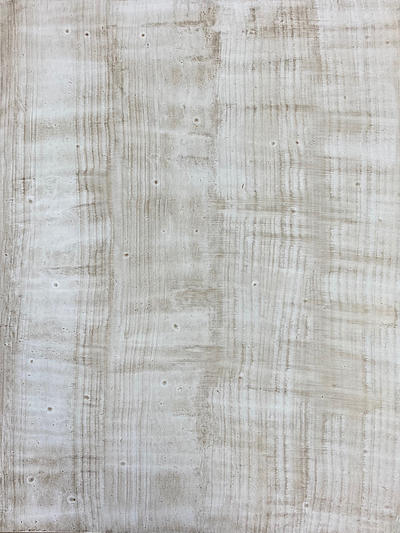

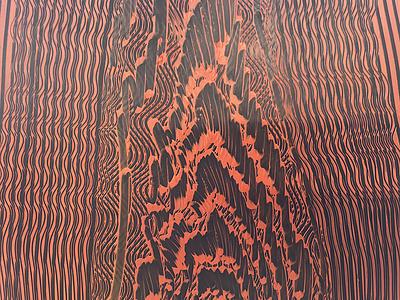

Factum Arte are masters of this kind of forgery, in its most creative sense. A non-profit foundation operating out of Madrid, they have worked globally to analyse and reproduce some of the most famous, delicate and revered pieces of art, sculpture and architecture. Their inventions to digitally capture and reproduce the colour, surface, forma and texture of an object lead us to question the value we place on authenticity. If a fresco now housed in a museum was intended to be viewed in the damp dark of a venetian church interior, what is the more authentic experience, the fake in the original location or the original on the wall of a museum?

We will spend the week primarily learning the techniques involved in the fakery of materials, whilst also reading, thinking and discussing our preconceptions with originallity and authenticity. We will be physically and digitally surveying an interior with the help of Factum Arte and also learning the techniques of trompe l’oeil painting with Fontana & Fontana. At the end of the week we will have all of the knowledge and skills to reproduce this room at the ETH, which we are offering as a Vertiefungsarbeit over the summer of 2020.

London has never accepted master planning and does not accept concepts of any kind. It is disordered, mercantile, opportunistic, at times vulgar but always with an eye for a refined detail. Whether in architecture or in fashion or even in landscapes, unruliness is the natural setting for supremely elegant sequences grafted into the clumsy and the unkempt so easily that a natural order must be hiding in plain sight. London’s tolerance and accommodating character, just like its citizens, is bound together by a perpetual natural history; parks, gardens and river that weave throughout London’s natural history joining humans and architecture to trees, grasses, flowers, birds, insects, clay and gravel, the past to the present, growth to decay, the visible to the unseen.

Walking from the inland west to the maritime east, we shall go in search of London, which despite its best efforts to avoid the singular in favour of the plural, has one body and one heart that can be found in every brick and every blade of grass however carefully or careless arranged.

London, 22–28 October 2017

max. 750CHF min. 12; max 21 students

24-29 October 2021

Price Range B (max. 500Fr.)

10 students max

The Ise Jingu Shrine in Mie Prefecture, Japan is a reproduction. It has been demolished and rebuilt from scratch on a 20-year cycle 63 times, holding it in a paradoxical state; forever new and forever ancient and original. Is the temple a fake? What is a fake? Forgery, fabrication, fake and feign all have their etymological origins in words for the inventive acts of shaping and moulding. Can we consider the art of forgery, then to be a valuable creative act, a form of cultural heritage?

The 1972 John Berger BBC series, ‘Ways of Seeing’ begins with the presenter cutting a face from Botticelli’s Venus and Mars, a disturbing and provocative act even seen on YouTube almost 50 years later. This face has however already been extracted and distributed millions of times in catalogues, posters, books, catalogues, films, copies and fakes through photography and reproductions. The meaning of a painting no longer resides in its unique painted surface, nor on its immediate context.

We know most of the works of art that we love by looking at them in reproduction. It is images of these reproductions that we look at in books and carry around in our heads, yet being face to face with the originals can give us a qualitatively different experience. Vernon Lee describes this real relationship with physical artworks as a spontaneous and organic attraction, an immanent and unconscious relationship with the things in her environment. But can a forgery incite the same phenomena? “The important decision to make when you are talking about the genuine quality of a painting’ explains Clifford Irving, biographer of famed forger Elmyr de Hory, ‘, is not so much whether it’s a real painting or a fake; it’s whether it’s a good fake or a bad fake.’

Factum Arte are masters of this kind of forgery, in its most creative sense. A non-profit foundation operating out of Madrid, they have worked globally to analyse and reproduce some of the most famous, delicate and revered pieces of art, sculpture and architecture. Their inventions to digitally capture and reproduce the colour, surface, forma and texture of an object lead us to question the value we place on authenticity. If a fresco now housed in a museum was intended to be viewed in the damp dark of a venetian church interior, what is the more authentic experience, the fake in the original location or the original on the wall of a museum?

Alternating between city locations and the workshops of Fontana & Fontana in Jona, we will split the week between handwork and headwork. The Fontana family have passed their buisiness and knowledge down through three generations and remain the experts in paint techniques in Switzerland. Marius, Olivia and Claudio will be instructing us on the replication of a material chosen and surveyed individually during the week.

Questions of authenticity operate within different value systems when they are translated to pixels; depth and texture now a sliding scale of contrast and brightness. Having spent a semester interrogating the limits of resolution, our eyes have adjusted to the smooth brightness of the screen. For a week in October we will return our eyes to the workbench starting with a blank canvas and a rich topic. Not only will we study and reproduce wood and stone in paint, but we will also meet in locations around Zurich and take the time to and read and discuss.

14-21 March 2020

Price Range B

21 students max

18-24 October 2020

Price Range

10 students max

This series of seminar weeks explores our physical and emotional connection with the world around us. Focusing on different materials and actions we will investigate the process by which things are made at both the scale of the factory and the craftsman. Literature, film, and technology will guide and frame the way we look at these processes of making and we will use our own hands and bodies to explore each theme. Weaving, Firing, Casting, Carving, Moving, Forging, Preserving.

We will work in small groups of 12 students and each seminar week will be accompanied by a specific reading which we will discuss over the course of the week. By keeping travelling to a minimum, each seminar week will be affordably priced below 500CHF.

This series of seminar weeks explores our physical and emotional connection with the world around us. Focusing on different materials and actions we will investigate the process by which things are made at both the scale of the factory and the craftsman. Literature, film, and technology will guide and frame the way we look at these processes of making and we will use our own hands and bodies to explore each theme. Weaving, Firing, Casting, Carving, Moving, Forging, Preserving.

We will work in small groups of 12 students and each seminar week will be accompanied by a specific reading which we will discuss over the course of the week. By keeping travelling to a minimum, each seminar week will be affordably priced below 500CHF.

This series of seminar weeks explores our physical and emotional connection with the world around us. Focusing on different materials and actions we will investigate the process by which things are made at both the scale of the factory and the craftsman. Literature, film, and technology will guide and frame the way we look at these processes of making and we will use our own hands and bodies to explore each theme. Weaving, Firing, Casting, Carving, Moving, Forging, Preserving.

We will work in small groups of 12 students and each seminar week will be accompanied by a specific reading which we will discuss over the course of the week. By keeping travelling to a minimum, each seminar week will be affordably priced below 500CHF.