The Good Life

The Good Life

Spring is coming. Trim the hedge. Prune the tree. Mow the lawn. Put the skis back in the basement and the car in the garage. The sun will shine, maybe too much for comfort. Irrigation is ready. Build a conservatory. Convert the spare bedroom. Working From Home. Open plan kitchen. Peloton. The house remains home, safe and sound. For now…

More than half of residential buildings in Switzerland - by number - are single family houses. The single-family house and the land it occupies is the least environmentally efficient settlement yet remains the aspiration of many. Excessive energy-use per capita from the house and the private transport that sustains it are just part of the widening gap between societal objectives of reducing carbon emissions and individual emancipation. To many, the single-family house represents the good life. To liberal urbanites, it represents the banality and wastefulness of the suburbs, which perhaps explains the lack of critical attention in architectural discourse. In fact, architects have condescended the suburb for decades ever since 1933 when CIAM declared it and all it contains “a kind of scum churning against the walls of the city”. And it is in part due to this deep-rooted snobbery that the single-family house developed its own design codes by mixing a cocktail of real estate value and aspirational taste away from the gaze of academic architecture. Yet, beyond the superficial cliches of dull conformity applied from outside, the suburban single-family house has and continues to represent a great opportunity to radically reappraise the architectural, economic and ecological contracts embedded in society and nature.

In the late nineteenth century, the single-family house, laid out within a suburban settlement of equals, was the laboratory of utopian ideas. Later in the last century, suburban self-build and self-sufficiency found great opportunities after the oil crisis peaking in the solar houses of the early 1980’s. Class, race, gender, sexuality have been more mobile here than the urban gatekeepers of culture will admit. You may not find the revolution on leafy suburban streets lined by neat houses standing on well-trimmed lawns but you can never be sure of where the imagination of bored teenagers will lead. For good or ill, Apple, Microsoft, Amazon were invented in suburban garages. Bowie and punk are profoundly suburban.

And while tech, music, art and literature have found fertile ground for experiment within the suburban idyll, architecture has kept it at arm’s length. One notable example stands out from the pack. In 1978, Frank Gehry started pulling his own ordinary 1920’s single family house apart in Santa Monica. The simple timber construction, common to almost every house in the American west, willingly released boards to his curious hand revealing the spatial sketch of a balloon frame onto which he would add others. Quickly, the carport became kitchen and structure became spatial. And the wilder his interventions became, the more typical the means he employed. There is nothing in the transformation that could not have been made by the original builder or a confident amateur. And there are no materials in the Gehry House that do not exist in blissful normality along that suburban street.

Now, we should not be looking to Southern California for lessons in design for an age of climate change, but we can learn that the seeds of reinvention may be found in the object needing change. We simply need to look at it meticulously, to understand it, to pull it apart (literally in the case of Gehry or conceptually using tools of design) to put it back together in a profoundly new way fit for a different future.

This semester, we shall stay near Zurich and redesign a normal single-family house. We shall search for the typical, not the exception as this is where we can find a new reality. We shall explore how architectural reinvention can turn the single-family house into a regenerative environmental type. The aims are social, spatial and natural. The means will be modest, circular, non-extractive and confined to what we find around us which of course includes the climate, the economy, the law and all the non-human species oblivious to property boundaries, but sensitive to appropriate habitat. The single-family house cannot be understood without the garden, which like the architecture it hosts, will be reimagined for new climates and ecologies.

Zurich Real Estate

The urban population in the City of Zurich declined during the second half of the twentieth century as house building in the agglomeration increased. Good roads and increased car usage helped a building boom that peaked shortly after the commuter railway lines joined the agglomeration to the city centre with even greater ease and speed. Half the buildings in the canton of Zurich were built after 1961.

The oil crisis of the early 1970’s provoked a first awakening to environmental performance in buildings followed by experiments with solar in the 1980’s. Architects in Switzerland, such as Ueli Schäfer, designed and built alterations to existing houses as well as new ones with new principles of passive solar design. These solar houses became the site of experiments. Vertical glazed winter gardens and Trombe walls added exotic touches to the basic typology. Careful use of solar orientation in relation to site layout provoked innovative solutions. The aims motivating solar houses could not be further from Gehry’s in Santa Monica but the means resonate; they share an interest in lightweight, efficient construction, bright daylit spaces with large open areas facing sun and sky. However, increase in the overall insulation of building fabric quickly replaced the exuberant spatial experiments of solar houses closing a short but inventive chapter in the story of the single-family house in Switzerland.

Changing regulations meant that, by the 1980’s, most of the ordinary single family-houses in the Zurich agglomeration were built with insulated cavity walls and double glazing. However, decades later, those houses fall far short of the performance needed if these settlements are to meet the energy and ecological standards required today.

Urban renewal has reversed the exodus from the city. The population in the city of Zurich is rising again provoking an ongoing demand in housing. Yet despite these changing demographic cycles, the single-family house is more popular than ever. A combination of Swiss protestant modesty and decades of low interest rates have enabled exceptionally high real estate value to be kept well hidden behind the apparent ordinariness of the architecture.

We cannot simply change the paradigm with metropolitan values of equity and collectivism. The suburbs have shown themselves to be highly resilient to change by design and good intentions. We will need to understand the underlying social values that cherish and protect the dream life in the single-family house. Interest rates are rising alongside global temperatures. These affect everyone and everything. If new models are to be found, they will come from within where needs meet desire.

Native genius in anonymous architecture

It would be wrong to describe suburban architecture in Zurich as anonymous and rarely can it be described as genius. Many architects have worked with care and dedication in designing houses for their clients. Yet this pioneering book by Sibyl Moholy-Nagy published in 1957 titled, Native genius in anonymous architecture can provide a mirror in which to reflect objectively on the qualities of an architecture, which while not anonymous, does not have a voice in academic architecture.

Written nearly a decade before Rudofsky’s Architecture Without Architects (1964), Moholy-Nagy seeks to identify the architectural qualities intrinsic to North American building traditions and design. She writes about what she sees; her gaze is forensic about construction and materials, form and climate.. Her attention to architecture in relation to climate and user anticipates the preoccupations of post-oil crisis environmentalism, solar houses and the contemporary search for a sustainable and regenerative architecture today.

Buildings are transmitters of life is the opening statement. And while the life of the people who design, build and use the buildings under examination is front and centre, the book is structured from the outside long before the Anthropocene was named, demanding new atmospheric taxonomies. Site and Climate leads to Form and Function, Material and Skills and A Sense of Quality enigmatically illustrated by the roof, corner, base and access (doors to you and me).

Moholy-Nagy’s chapter are not only useful in offering a way to see and understand architecture, it maintains a critical bite into a vernacular too often romanticised by Modernism. She does not spare the ‘bunglers who studded the land with eyesores’. She is attentive to deep cultural meaning, praising histories that naturally embody climate, use and change while wary of the ‘tyranny of tradition’.

We can use NGIAA to look differently at the single-family house. To see it as an environment of material events embodying social value. To see it as a place of invention and tradition, often wasteful but full of potential. Above all Moholy-Nagy draws narrative from climate to door detail that speaks to the most pressing issues of today and tomorrow.

Where is the House of the Future?

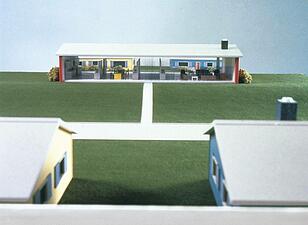

As Sibyl Maholy-Nagy was completing her book, Alison and Peter Smithson constructed a full-scale mockup of The House of the Future (1956) an apartment for the Daily Mail Ideal Homes Exhibition. Their vision of the future: living zones focused inwards towards the neatly clipped lawn of the internal courtyard was called the ‘House for the Future’ and hinted towards a high-density way of constructing housing for the future dwellers of the planet. Whilst they were drawing their visions, masses of single-family homes were being constructed on the outskirts of urban centers to house the post war boom in population. It turns out that the house of the future is already built.

The Smithsons’ House of the Future was a technical fix to a modern way of living, fully automated appliances and furniture making everyday life as smooth and efficient as possible. Today’s high tech follows the popular discourse and aims not at spatial economic and environmental efficiency; green gadgets to reduce your bills, carbon footprint, and guilty feelings. We will be looking back at vernacular architecture, as well as 21st century attempts at upgrading the suburban house towards the sun’s natural energy in order to find our own attitudes to climate adaptations.

Space and resource hungry, yet containers for many ways of life: hHow do these single-family homes step into our future whilst remaining critical of the technological quick fixes marketed at their owners?

The houses built in the Zurich suburbs after 1961 contain all of the hope, aspiration and pitfalls of the domestic dream. Picture the most generic house you can think of in the Zurich suburbs. Its walls are most likely render on brick, or concrete, or directly on insulation, its roof is probably tiled. Although unique in many ways, it is undoubtedly very similar to the one next door, but not because of a vernacular tradition or as a response to the particular microclimate of the site, but because of markets, supply chains, and current tastes. Through looking at the suburbs can we introduce a building culture which can induce genuine sustainability?

Now imagine a section drawn through your home and expand the section all the way to the site boundaries, hedge to hedge, so as to include the suburban house’s inevitable companion: the back garden. The borders of these neatly parceled gardens are fiercely defended by their human owners, mostly respected by their domesticated animals, yet totally ignored by all other life. Our task will be to guide this suburban territory towards a future where cohabitation is radically increased.

You will form an attitude towards the sustainable construction of the house’s future. You will use your architectural skills, analytical tools and critical eye to renovate the Zurich single family house studied during the Atlas without losing the aspirational qualities of a house in the suburbs, turning the private property into a new kind of utopia.

Your design work begins by taking the building apart during the Atlas, and these drawings, models and photographs already contain the fingerprints of your own ideology. These documents are the departure point for the work on your renovations.

Atlas

Our project will start by making an Atlas of single-family houses around Zurich. And following Moholy-Nagy, we shall tie these studies in construction and space to the landscape, resources, uses and climate they belong to. We shall survey a series of typical single-family houses of different sizes, ages but built since 1961, materials and architectural language. From the interior space, we shall look vertically at the ground below and the sky above. Horizontally we will extend the interior into the garden and territory within which it stands.

House

We shall then look to transform the physical fabric of the single-family house as an act of radical care. How can thermal improvements pave the way to social change? How can the existing create its own resource? Can the eccentricities of individual suburban developments be a source of ready-made design ideas?

This will be a semester about making, about Material and Skill, which of course implies craft, resources and economy. The design will include the living landscape which extends around the house eventually describing the atmosphere. There will be constraints. There will be a budget, a carbon budget and a financial restraint. There will be the law. The constraints may even change during the semester and demand another cut. Constraints will be, to use the OuLiPo’s famous credo, the source of invention.

Garden

We shall continue work in the garden, between Seminar Week and the Easter break. Here, just like in the design project, we shall take an existing object apart in the old garden and reassemble it in the new. The Gumno is a circular bench/table/stage made for coming together as a group. It is too large and heavy to move in one piece. How and along which lines should one break and put back together the structure again so that it is better than the original?