Heat

Heat

It may seem like a cruel irony today to discover that human body temperature has dropped by half a degree over the past 150 years as climate change causes global temperatures to rise by 1.5 degrees and more. Partly thanks to reduced sickness, fever, sedentary lifestyles and climate control our internal metabolism produces less heat. And climate control is just one of the myriads of industrial inventions in search of comfort which have led to atmospheric temperature rising. Heat is the most complex phenomena of our times; the heat received from the sun’s burning core is fundamentally life giving yet heat threatens our very survival.

Heat, which is both a description of energy in transfer in thermodynamics and a measure of temperature and comfort, is without scale. From the sun’s near infinite source to the pain of frozen finger tips, it is everywhere. In our bodies, our earth, our atmosphere and at the heart of architecture as we gather around a hearth or retreat from the midday sun. As well as protecting us from the elements and hostile beings, architecture has evolved to manage the capture, storage or exclusion of heat. Shading, insulating, ventilating, heating, cooling have all directed the transformation of material into architectural culture. Whether vernacular or representational, the methods of managing heat are deeply encoded in the language of architecture from visual customs to precise performance and contemporary norms.

In pre-modern times, heat or lack of was a natural component of place. Regions developed their own architectural traditions which in construction and architectural articulation. From thatch roofs in the north to insulate or deep masonry walls with small with small openings in the south to keep heat away, every element of architecture was tuned to place extending into the layout of rooms, gardens and the very fabric of the city created organic microclimates in search of human comfort. Carefully balanced environments extended into the social rituals they would host.

Industrialisation fundamentally upset the natural order. Expanding cities opened the era of fossil fuels with dire consequences for the environment and public health. Seeking to heal the injustice and ill health of industrial society Modernism turned to the sun, fresh air and sanitation. The sanitorium became literal and symbolic means to wellness. Long white horizontals facing the sun gave patients spaces to breathe under the warm and healing solar rays. Lightness and transparency gave us the language of wellness which export the wellbeing of the sanitorium to all building types of the Modern age. Hospitals adopted the new architectural horizons as did schools, housing and houses, museums and offices throughout the world regardless of climatic of social predisposition. And if comfort was not easily achieved through passive means, mechanical heating and cooling would compensate their shortcomings with impunity. Heat and coolness were no longer the preserve of nature but transactable just like all the fruits of industrial society.

Today it is Modernism that needs healing just as much as the environment it sought to emulate. Lightness of structure and luminosity is now losing and gaining heat we can no longer afford. Corrosion and condensation conspire to consume ever more energy in an attempt to meet norms designed by modern men for modern men. But no one is comfortable, not the planet, not even the men.

But our cities are full of great works of architecture, still willing to serve. Building are full of grey energy and as well as the energies of the architectural imagination, innovation and optimism. They simply need more care to adapt to our rapidly changing times. Refurbishing Modernism is an opportunity to rediscover the sun and the earth in communion with all the human and non-human communities that share our planet.

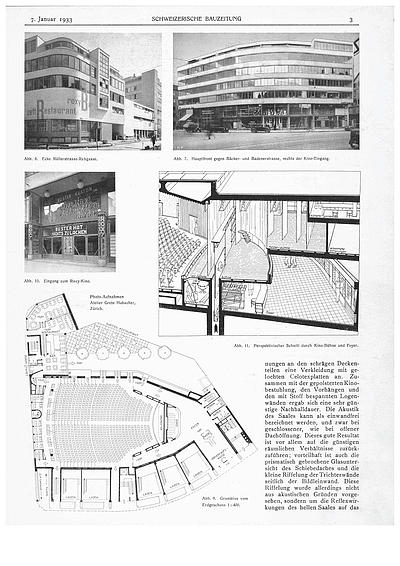

The therapeutic environment of the Alps combined with escaping the ravages of twentieth century conflicts gave Modernism an ideal setting in Switzerland. Zurich has an enviable tradition of Modern architecture that serve all walks of life. Located near the river Sihl, Flora Steiger-Crawford, the first woman to graduate in architecture from ETH in 1923, along with Rudolf Steiger and Carl Hubacher designed Zett-Haus, an office building and cinema with all the elegance promised by the new architecture of the 1930’s. Defined by a long, curved façade of horizontal glazed bands, the sanitorium type was adapted to form part of Modernist urban set piece. Much of the innovative concrete structure, fine glazing and cinema with retractable roof has been effaced in successive refurbs. Every Zurich resident has passed Zett-Haus and many have used the shops in the ground floor or watched film in the cinema but the bravura of the architecture is lost. Another refurb looms to maintain contemporary norms and keep decay at bay.

This semester, we shall propose an alternative to the erasure of Modernism by unsuitable careless refurbishment or worst still ersatzneubau still all too common in the city. Both the building itself and the neighbourhood in which it stands suffer for heat. The building oscillates from heat loss to heat gain. The cinema has renounced opening to the sky. The ground around it is sealed preventing ecologies and water to regulate the environment naturally.

In A Cautious Prometheus (2009), Bruno Latour reflects on how design can address the age of climate change. Unpicking the extreme scales in which design operates, he notes that design is only ever re-design. And that such a realisation needs to be put to work with caution and care to provide the antidote to Modernism’s quest for the revolutionary new. Modernism is no longer new and its preoccupations could be further from our own. Indeed, the future avantgarde will be dealing with past or at least with the existing, in order to radically realign with a more sustainable, caring natural course.

So our design method will start carefully, incrementally. We shall start with documenting what already exists. We shall examine and measure Zett-Haus as it is today. We shall examine archive drawings, specifications and photograph documents to reconstitute its origins. This survey will be the Atlas, a collection of drawings, photographs and mock ups to describe as fully as possible the promise of the new. However, all surveys are incomplete, so the Atlas is also a critical object of design. Omission contributes as much as inclusion.

The Atlas will then be the site for disassembly; for taking the building apart component by component and stripping away the sealed grounds that surround it to reveal a new reality lying below the surface. We shall excavate the contemporary condition until we find the spaces ready for tomorrow. Piece by piece we shall re-assemble a renewed version of Zett-Haus adjusted to a new climate, a new society, a wider ecology. A new version of Modernist heritage that accommodates heat and coolness as productively and naturally as its biological context.

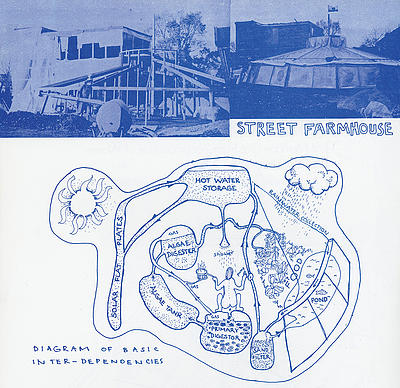

Porosity is central to the environmental recovery of architecture as it is to the city. The constructed fabric of the building needs to be uncovered and excavated in order to be reassembled in harmony with the sun, the user and the city. Around, species of plants, insects and mammals can rediscover habitats covered by asphalt. Construction has never been so important. Perhaps now is the moment to welcome them into the heart of things by looking at urban development in reverse. But not a return towards origins per se, but to acknowledge that the world is cyclical and after the growth comes decay followed by recycling in order to grow back strong, more diverse and resilient.

Urban porosity may be closer than we think. Zurich is completely restructuring its heating infrastructure in a new set of district heating systems that will end its dependence on fossil fuels. Over the coming decade, whole neighbourhoods will be punctually excavated to install the new systems and offer unofficial opportunities to leave open more ground. The new heating systems may therefore be more radical than technological substitutions. They could give rise to new environments, and their heat is carbon free, it may even lead to new standards of performance for the built fabric and communities they serve. Those modern standards created to ensure an equitable level of comfort for all, but destined to ensure energy is overused, could be re-scripted for a more diverse community.

But as much as this question may be about the future of wellbeing and the environment, we shall approach the project by direct means of architecture. We shall initiate a series of constructional operations on the building; the first is to record what is there through the act of surveying; measuring, photographing and drawing what we see. The second will be to excavate material from the building fabric to create or recreate new spaces for new ecologies. And the final stage will be to re-inhabit the excavated building to propose a future which contributes to the human and non-human ecologies of the city. We shall use full size prototypes to examine the potential of the existing, to adapt it with minimal means and create new exchanges between heat and cool.

We will conclude the semester under the warming rays of spring working together in the garden. Last semester the 75m long plot of the new garden was marked and transformed into a three-dimensional textile with piles of soil, clods of earth, cuts and ditches. May 2022 will see us work with, within and around this existing project to create a life support system ready to host the transplanted 6-year old garden. With water as our focus we will create a networked system to collect and channel the rainwater and snow melt across the site to nourish the soil, adding new threads to the rich tapestry of the last semesters’ projects.