The Great Interior

Altering Architecture

Pula, Croatia

“Bricolage may be, quite simply, the making of things in the full and liberating awareness of how little we know.”

Irénée Scalbert

Pula and the Brijuni islands are one of the few remaining unspoiled Mediterranean landscapes. Their survival is largely due to the particularly complexity of Balkan history in the twentieth history. Istria was annexed from the Austro-Hungarian Empire into Italy in the first few decades of the century as World War I violently rearranged the old world order. After the second World War, Yugoslavia, under a form progressive non-aligned socialism, found prosperity and stability outside the binary polarities of the Cold War. But tragically the century closed with a terrible civil war from which Croatia and its neighbours have emerged in the fold of widening European Union. With peace and a new alignment with the economically liberal west, the Istrian landscape is now a new resource in the Mediterranean tourist market.

Tourism is not new in Istria, but it is growing at an unprecedented rate. As shipyards, naval bases and even agriculture decline, the scenic townscape, beaches, warm seas and wilderness are the new commodity. Development associated with increasing numbers of visitors is putting the very thing which brings holiday makers to Croatia in peril. Much of the Mediterranean has been profoundly damaged over the past forty years by barriers of development in search of the view. The view is the ultimate rhapsodic consummation of the environment by the market. Now we can own to the horizon: the view is consumption without responsibility.

To make a building is to make the territory. From a single step taking you from earth to dwelling or a humble windowsill keeping rain and cold outside while inviting light, design crosses culture with climate to define how we dwell. And whether built or grown, our environment is designed and constructed in a combination of modest fragments and great ensembles.

Based on last semester’s foundation, we will return to Pula to alter existing situations into a unknown, bright future.

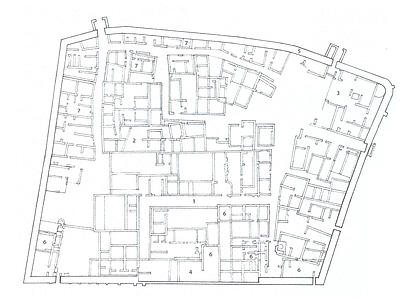

In the Atlas of Pula you have described a complex territory through antiqities, natural and artificial ecologies, infrastructural and industrial landscapes and an intricate network of austro-hungarian military forts. We have seen how small interventions could radically question and transform that territory with new meaning and definition.

We have selected five existing buildings dealing with the larger territory of Pula for you to propose projects related to new kind of tourism. You shall re-use, conserve, convert, take care, transform, extend, alter the city around it.

The proposals will give definition to what is city, caring for what exists (architecture and landscape) but without - to paraphrase Alberti - preventing what has yet to come in the future. Instead we will design the future of these buildings.

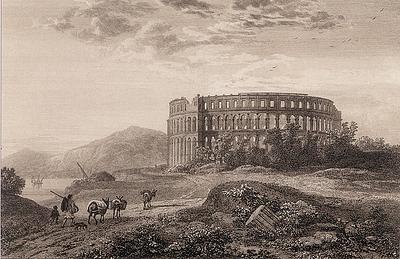

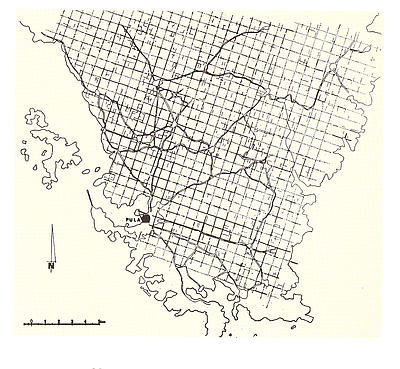

The ancient architecture of Istria on the other hand, uses natural resources for social, civic or even spiritual progress. Lime stone cut from the hills of Istria were carefully carved by the Romans to form amongst the finest colosseum, temples and villas east of Venice. Nearly two thousand years later, the Austro-Hungarians built massive circular stone walls to fortify the Istrian coast and islands against the Venetians but in the end, destruction did not come from the sea. It was the Allied bombing during World War II that destroyed part of the city from the air, inadvertently sketching out voids in the city that would become Pula’s civic spaces. The exquisite Roman Temple of Augustus (first century AD), reconstructed in the late 1940’s using anastilosis, is now the centre-piece of the Forum where tourists enjoy café society under the shade of generous parasols. The Forum, the Colosseum, the Amphitheatre, the port and the market are a few of the neighbourhoods at the foot of the fortified hill that make Pula a kind of urban archipelago analogous to the real chain of islands lying offshore. The rocky coast and archipelago provide strategic visual protection to a fertile inland territory gridded by Roman administration two thousand years ago. It is still just about visible today.

Looking out from the hilltop fort at the centre of Pula, an archipelago of islands bears witness to the strategic military importance of Pula since Roman times. Lying in the turquoise sea, the natural beauty of the Brijuni islands promise more innocent pursuits of pleasure and leisure for thousands of tourists every year. However, hidden under scrubby woodlands and deep in the rocky outcrops of the islands, great forts crumble. Some are accessible intensifying the landscape with the pleasure of ruins. Most however lie in splendid isolation on deserted islands still owned by the Croatian Navy long after the Mediterranean ceased to be a European battle field. The forts present paradoxical architectural objects; on the one hand their massive circular walls constructed of intricate cut stone is an expression of pure abstract form, yet, on the other, they morph seamlessly into the wooded hilltops in which they become invisible. They are monumental and modest, balancing constructed physical mass above excavated tunnels, stairs and chambers cut deep into the mountain’s mineral geology. As they extend into the landscape the forts disappear into landscape.

But it is no accident that the landscape of Pula and neighbouring has attracted generals for millennia, and tourists in equal measure. Gun slots in turrets and bunkers are as picturesque as any belvedere. The visual command over the landscape for military purpose layered over many centuries matches a more recent, even contemporary picturesque desire; to turn the world into a picture, to frame it and own it, whether for power or for pleasure, while pushing nature beyond human action.

These islands of wilderness in the Mediterranean embodies the picturesque landscape in extremis. It has captivated the human imagination for centuries merging the forces of natures with antiquity with the origins of European civilisation. At best the former will be crumbling elegantly into the latter like the Romantic images of ruins fashionable in the nineteenth century. French and British surveys of Pula from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries reveal an idealised Mediterranean landscape as magnificent as the more famous representations of Rome, Naples and Split and became an important stop in the Grand Tour, presumably continuing on to Split, Dubrovnik and Greece. The Grand Tour was the exclusive preserve of the upper classes in search of culture and adventure.

We shall spend the year researching a new architecture and landscape that will contribute to the fragile layers of this precious Mediterranean territory. We will work with the archipelago literally and metaphorically. We shall make an Atlas of Pula and the islands of Brijuni; a survey which will combine into a single collective document the past and present environment, defining territories alongside fragments of architecture and ecologies that together create a new reality. In the first semester, we shall use the Atlas to explore a future of the archipelago. We will ask you to design a small building within this natural sanctuary full of fragments of the past. The island offers escape, isolation, even abstraction where architecture can grow new individual shoots unencumbered by mainland convention and continuity. It is no accident that the island is home to Utopia, Robinson Crusoe and the darkest prisons of history and fiction.

We will follow the individuality of island architecture with a metaphorical archipelago within the city of Pula. From the treasures of antiquity to the end of industry, distinct urban islands describe a town of multiple identities. We shall look to integrate future of tourism within the civic fabric of the city where the view and the viewer share the same environment. Within the declining industrial infrastructure lies great potential for re-invention from within. Lost industry releases new spaces and potentially new forms of tourism beyond consumption. Our reconstruction will not re-lay the stones of ancient temple but we shall look to materiality and construction to guide us towards a new architecture of civic and civilised tourism.

We will continue building and planting in our experimental garden at ETH which provide a real engagement in the interactions of architecture with landscape over time – a full scale, real-time case study in making and the layering of history at the heart of the studio.

There will be a short obligatory studio visit to Pula on the 6th till 9th October; cost 200 CHF (hotel and transport included).

Learning from the existing landscape is a way of being revolutionary for an architect. Not the obvious way, which is to tear down Paris and begin again, as Le Corbusier suggested in the 1920s, but another, more tolerant way; that is, to question how we look at things.

Learning from Las Vegas, 1972, Venturi, Scott Brown, Izenour

Outside the interior lies just another, larger, interior. An interior which contains all nature. Until recently, the story of the city has mainly favoured the centre. In the centre architecture found the place for political and artistic representation. The city wall kept hostile outsiders out and concentrated power within. The edge served as a place of defence and exclusion even without a wall. But the emergencies of climate change and globalisation demand another more integrated solution. Architecture needs to find a new purpose and means and today, it is the edge, rather than the centre, which holds the promise for a new type of interior that includes rather than excludes; an interior which contains the whole landscape and our lives within. We shall go in search of utopias on the edge, a new integration of architecture and landscape on the fringes of Zurich. Much of it is already there in communities and ecologies just far enough from sight to escape from a given form. But what is it? It is not a park; it has neither its design or singularity. It is not a garden although it contains many. And it is certainly not a pre-existing nature found on the edge of Zurich although it is perfectly natural. This place is made, is maintained and is regulated yet it feels loose, informal, open, public and even occasionally refreshingly scruffy. It is not civic yet it is cultivated metropolitan space. The landscape of the edge could be seen as a great work of bricolage where a world of multiple uses and environments loosely and informally defined by fences, boundaries and architectures within an accommodating nature.

We shall make a collective Atlas of the Edge, the ecologies, architectures, construction, materials, botany, gardens, working spaces and social lives which find common cause with nature. At the heart of bricolage lies the inventory of existing material and means. If the task is at the scale of an individual maker the inventory is ostensibly simple: materials and tools. When looking at the scale of territory, the architect’s inventory is the survey, both record and fiction. The first act of design is to observe and document how the very smallest construction is fundamental to defining the territory and conversely how the bigger conditions of landscape, topography, climate and collective human affairs determine the small actions of everyday life.

We shall start where all of architecture began; in the garden, in our garden at Hönngerberg. We will survey and observe the nature of existing elements and design and build a new structure for the edge. We shall see how the centre has pressed up to the edge and left a space in need of attention.

Once built, the garden project could be seen as a primer for a larger investigation on the edge of the city. To observe how multiple uses and communities have settled within a richly constructed nature and, as the authors of the Garden City believed over a century ago, this integrated landscape may be the site of utopia. Bruno Latour’s Cautious Prometheus states; “What no revolution has ever contemplated, namely the remaking of our collective life on earth, is to be carried through with exactly the opposite of revolutionary and modernizing attitudes. This is what renders the spirit of the time so interesting… the revolution has to always be revolutionized… the new “revolutionary” energy would be taken from the set of attitudes that are hard to come by in revolutionary movements: modesty, care, precautions, skills, crafts, meanings, attention to details, careful conservations, redesign, artificiality, and ever shifting transitory fashions. We have to be radically careful, or carefully radical... What an odd time we are living through.”

We will ask you to develop a radical architecture based on the world that surrounds you and. We shall see that beyond the edge is not outside, in fact it is just another inside, an interior which is designed, constructed inclusive and productive. In essence, natural.