Siedlung

Siedlung

By 2050, Switzerland is anticipated to grow by 1 million people.

By 2050, Europe has agreed to achieve a climate-neutral building stock.

If Switzerland is to accommodate one million more people over the coming generation, every community from city centre to countryside will need to play its part. Ambivalent about big cities, Switzerland has evolved a highly sophisticated, decentralized version of density in the Siedlung. But like so many things evolving naturally, Siedlungen are difficult to define: residential, but not simply housing. And while never completely urban in spirit, they are found in cities. Not bucolic rural, yet they draw qualities from the countryside. Public and private distinctions are of no help, as a Siedlung can be either.

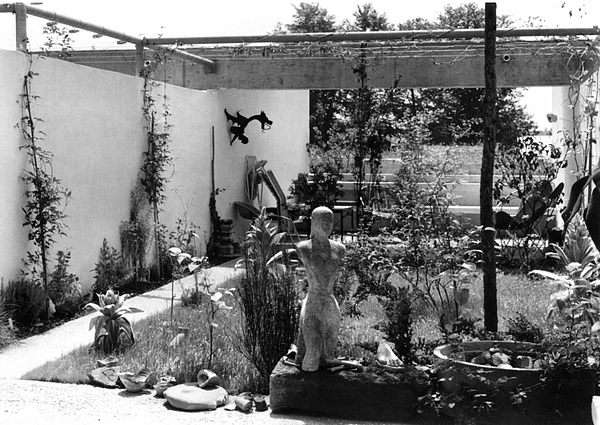

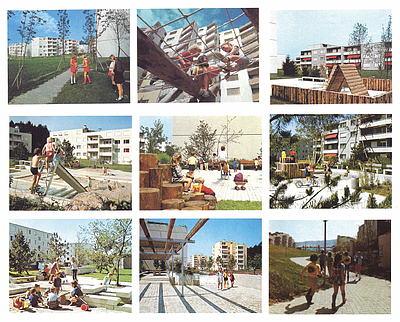

There are many exceptional Siedlungen in the story of Swiss modernism. Could the generosity of social and landscape infrastructures and the architectural imagination that define the finest example be more than nostalgic utopias from better times and support additional communities – both human and non-human? Could the best Siedlungen be the beginnings of greater things for the greater good without consuming more land and yet more resources?

This semester we will look closely into three Siedlungen, which emerged more or less at the same time, were significantly shaped by the social, architectural, and industrial transformations of their era—not only but also by the oil crisis and recession, which affected them in different ways. All three Siedlungen are situated on the periphery of urban centers—neither fully rural nor suburban—yet they seek to combine elements of countryside living with a high density, creating a sense of the proximity of the cities, where communal and private spaces are defined, creating cohesive communities that emphasize shared amenities.

Being housing experiments, Siedlungen were mostly established in challenging locations in terms of the landscape: On steep, clayey, moist slopes of conglomerate and loam, moraines formed by the Linth glacier, such as the Rüdiwiese in Adliswil. Or in former river floodplains in the lower freshwater molasse, such as the Webermühle in Neuenhof, which is placed in a topographically complex site and enclosed between road and railway infrastructure, heritage and industry, river and forest. Or in transition to former marshland such as the Siedlung Höri in Scherz, within a typical Mittelland Swiss landscape, rich in water streams and springs, which stumbles between single house entities and agricultural fields. All three Siedlungen are therefore part of an overarching hydrological system and have the potential to play an interlinking role for plant and animal societies as well.

Their densities vary greatly, as do their visions of communal living, their relationship to the landscape, their sense of community, and ultimately, their ideal of housing. Their distinct architectural language does not merely express a contemporary tendency but rather reflects a specific vision of housing and living. Characterized by a strong material identity and a striking presence in the landscape, each siedlung carries its own material culture—sometimes defined by a drive for efficiency, resource scarcity, or a desire for uniqueness.

Despite their serial character, they propose their own approach to housing and the negotiation of private space within a communal realm.

In doing so, they represent one of many approaches to responding to social changes and new ways of living, and ultimately offering a solution to urban migration and its housing crisis of the time.

Yet, beyond their self-sufficiency and completeness, existing Siedlungen represent an untapped opportunity to significantly expand housing in the coming generation. Doubling the density of Siedlungen across Switzerland could provide housing for over one million people. And while this could be a significant contribution to communities and individuals it is unsustainable if it comes with a reduction of biodiversity.

It is not a question of choosing between human and non-human but of integrating them in a single idea of coexistence, of doubling the population and doubling the density of biodiversity and all the species they can support. The rules of engagement will change. Boundaries, limitless below ground development, density and design regulation needs to be re-written.

A new coexistence with flora and fauna leads us to question our relationship with nature and our attitude to the cultural landscape that has evolved over time. What does coexistence mean for the identity - in a country where national identity is strongly celebrated with rural, farming life? And what are the new open space typologies, which allow a coexistence?

For the master thesis, we shall explore how architecture can open new ways of living and sharing. Using Siedlungen as case studies, we will explore both the typical and the exceptional—where new possibilities for living may emerge. We shall explore how we can find in our surveys architectural reinvention to densify these Siedlungen. How do we implement the urge of densification within the built fabric and architectural heritage? The aims are social, spatial and natural. The means may be modest, circular and non-extractive but the economic, social and legal implications will be radical.

A Master Thesis Semester in collaboration with

Professur Voser, Professur für Landschaftsarchitektur